Beyond Delivery: How Dronamics Built a Drone Platform for Europe’s Next Decade

Persistence is often framed as a generic startup virtue, but in Deep Tech, and especially in aerospace, it’s a survival mechanism.

Founded in Sofia, Bulgaria, by brothers Svilen & Konstantin Rangelov, Dronamics is the only European company that designs, builds, and operates large, long-range drones purpose-built for freight.

Today, Dronamics is a full-stack aerospace business and the world’s first cargo drone airline with a licence to operate in Europe, where previously none existed. But building a multipurpose aerospace solution out of a startup, in a sector where most prototypes never leave the runway, takes more than technical vision. The last decade has been an endurance exercise: building hardware in a continent that’s still learning how to back it.

Speedinvest first backed Dronamics in 2015, after the company won an international startup competition in Austria. The company then mostly bootstrapped and built one of the most cost-efficient businesses in a market full of expensive failures. Earlier this year, Dronamics was selected for a €30 million EU Investment designed to advance strategic technology in Europe, further validating the business’s consistent and pragmatic approach to growth.

From Concept to Cargo Pioneer

Dronamics’ story is one of persistence through adapting to changing circumstances.

In an era where most startups scale with software, Dronamics built an airplane. And not just any airplane, one designed to turn unused airfields into local cargo hubs. As Svilen puts it:

“Our full-scale Black Swan is the only large drone, made in Europe, that can cover the entire EU in one flight, carrying the same payload as a small delivery van. It doesn’t need a fully-operational airport or new infrastructure as it can land nearly anywhere with a 400-meter airstrip.”

Dronamics identified some major opportunities to change an entire industry; its Black Swan model enables advanced air logistics, which is particularly beneficial for remote and underserved locations.

In Bulgaria, the capital Sofia serves as the country’s main gateway for air cargo, but as Svilen notes, there are 105 underused airports and airfields across the country that could become local hubs for the flow of goods. Because Dronamics’ drones are smaller than traditional aircraft, their ability to land in more destinations is a massive advantage for the company.

It’s not just a problem unique to Bulgaria. As Svilen adds: “Only 7% of airports worldwide have regular flights, placing enormous pressure on these hubs, while approx. 50,000 airfields that have the potential to be local cargo portals are underused.”

The lesson? Innovation doesn’t always mean creating something new; sometimes it means unlocking what’s already there. By turning 50,000 underused airfields into potential logistics hubs, Dronamics built its model around Europe’s forgotten infrastructure rather than fighting to replace it.

In addition, analysts project the global drone delivery industry will reach $39 billion by 2030, but getting there depends on companies that can survive the long development cycles. Dronamics is proving that patience can, eventually, pay off.

Drones and Dual-Use

Dronamics’ use cases naturally expand beyond cargo and freight.

Beyond logistics, Black Swan could be deployed for disaster relief, firefighting, and civil protection in countries frequently impacted by natural disasters. The company has a partnership with Japan’s Kawasaki, for instance, which is developing an advanced aeroengine to improve the Black Swan’s market-leading specs further.

From Dronamics' initial mission focusing on connectivity, the company has expanded to a platform approach, enabling dual use, which has numerous benefits for Europe. This flexibility and focus on staying pragmatic have helped Dronamics adapt to new opportunities.

“Drones are by definition dual-use technology,” Svilen said. “We started considering defense seriously when Europe started taking its defense seriously. We have always known that the technology we have developed could be put into use to protect Europe, and now is the time that Europe needs solutions like ours to defend its way of life, so we are here to serve.”

Between 2014 and 2024, EU defense spending rose by $145 billion, according to the European Defense Agency. In 2024 alone, the EU spent $98 billion on defense hardware and $14 billion on defense software, meaning Dronamics could yet further benefit from its multi-faceted, platform approach to operations.

Dual-use is more than just an opportunity for growth; it’s also a regulatory and ethical balancing act that many companies struggle with. Dronamics’ advantage is that the same aircraft can serve civilian and public-sector missions without changing its core architecture.

Building for First Principles and Flexibility

Dronamics approached the problem based on first principles thinking. “The laws of people can change, the laws of physics cannot, so our aircraft design decisions are led by that,” Svilen said. “We set out to build the most aerodynamic, fuel-efficient, and robust aircraft there is. Pragmatic is our guiding principle.”

The company’s approach to design keeps Dronamics vertically integrated, which can be spun as both a constraint and a competitive edge.

As Svilen puts it: “We had to recreate pretty much every part of the ecosystem, not just start a business, and that is why we became very vertically integrated.”

That vertical integration helped them innovate faster, but it also demanded patience, cash, and conviction. For founders, the lesson is that control can accelerate progress if you can afford the cost.

“Having design, manufacturing, and air operations all under one roof is a huge advantage because by keeping the feedback loops shorter, you can innovate faster,” Svilen added.

Dronamics began its platform focused on cargo, with an emphasis on cost. Customers can be price-conscious, meaning things like fuel efficiency, operating costs, and product costs have to be kept down.

“This cost leadership allows us to offer the platform with the widest range of applications on the market, and that is very important in a space where new designs can take many years to commercialize,” Svilen added.

“The fact that from a government customer POV you can use the same platform to do anything from border control, maritime surveillance, firefighting, disaster relief, and more, is a great advantage, as it saves taxpayer money and gets very important tasks done.”

Many deep-tech founders start with a single use case and only later discover broader applications. Dronamics did the reverse, designing for flexibility from day one. This not only opened doors to new verticals like defense and disaster relief but also insulated the company from market cycles in logistics or cargo.

As Svilen puts it: “So none of this is a pivot, rather a natural next step of us developing the Black Swan as a platform for multiple solution sets vs a single vertical.”

The takeaway: building a platform mindset early can turn a niche idea into a durable business.

The Realities of Scaling in Europe's Deep Tech Ecosystem

Dronamics is a product of Europe’s deep tech innovation ecosystem. Where solving the biggest problems can be highly research-intensive, expensive, and with long horizons to any potential product.

“Hardware is hard, and aerospace is even harder. But the mission is more important, and to date, we are the only ones to have repeatedly designed, built, and tested large cargo drones, made in Europe,” Svilen said.

“It’s not for everyone, and this is perfectly okay; it takes a certain type of maverick.”

The lesson here is clear. Solving complex problems takes time, and persistence is key to building something that stands the test of time. In many ways, it’s also a reflection of the state of how Europe approaches funding for difficult projects.

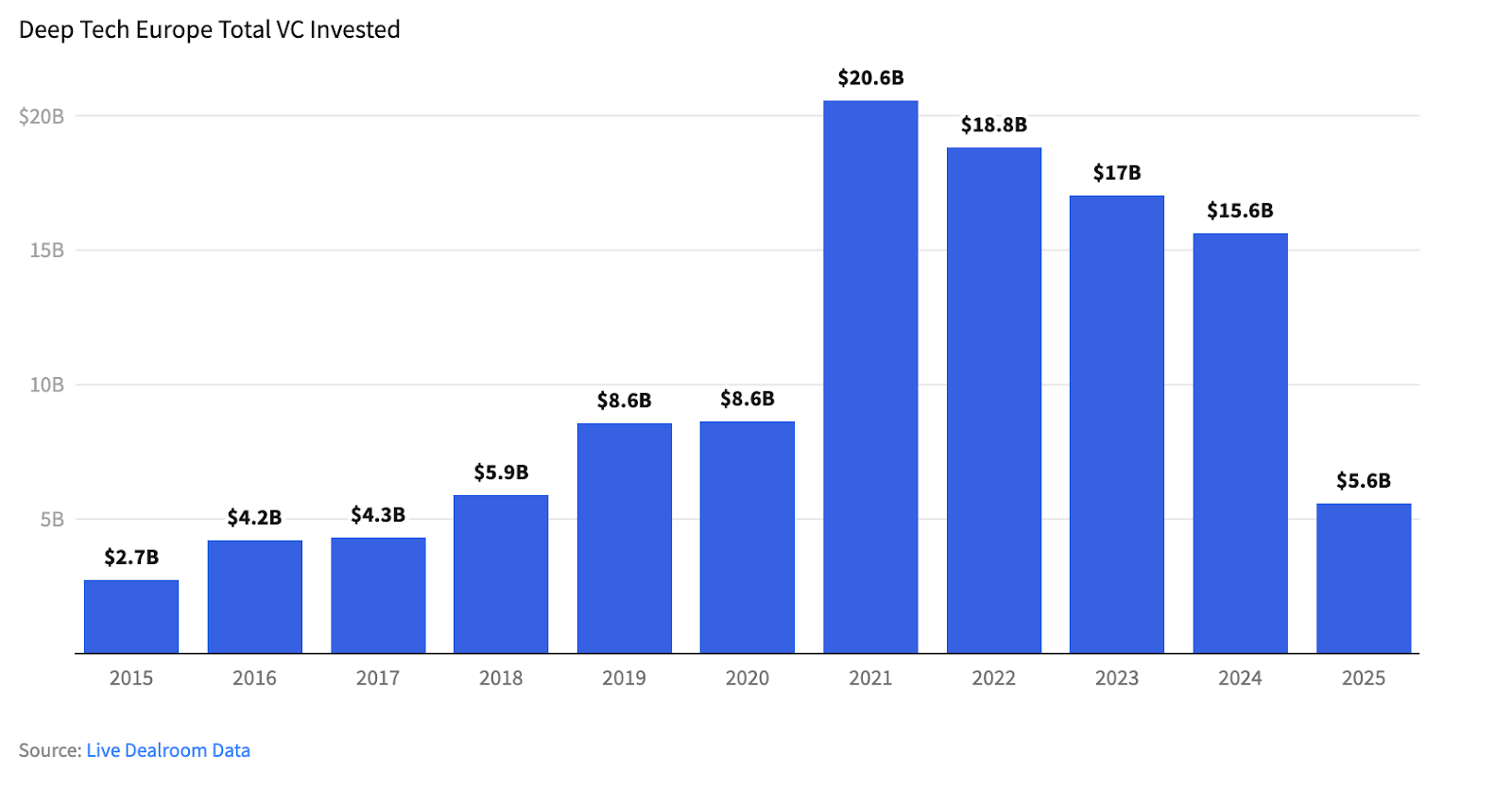

Deeptech funding exploded during the Covid-19 pandemic, but when Dronamics was selected for an equity investment of up to €30 million under the Strategic Technologies for Europe Platform (STEP), a flagship initiative of the European Innovation Council (EIC), it helped to demonstrate the crucial role that public, alongside VC, funding has in promoting innovation on the continent.

But public funding also comes with its own timelines and requirements. The founders who succeed in Europe aren’t the ones who rely on it; they’re the ones who learn how to combine it with venture capital without letting either dictate the pace of development.

In Europe, deep-tech scaling is rarely purely private. The smartest founders learn to navigate both sides, grants, tenders, and private rounds, as part of one capital stack.

“Public funding has a dual role, capital allocation as well as aligning societal and economic challenges with policy and technological solutions,” Svilen said. “This year has been an awakening one for the EU... It’s about moving quicker and with decisiveness.”

For a company that previously bootstrapped for many years before raising funding from Speedinvest, alongside Founders Factory, Eleven Capital, and, most recently, the Strategic Development Fund (SDF), public investment now complements a capital stack built to scale strategic European technology. It also serves as proof that European industrial policy can enable frontier tech companies to scale as the continent looks to match capital with conviction.

Resilience and the Maverick Mindset

After more than a decade, Dronamics is still an outlier in a space littered with grounded prototypes and failed moonshots. Its story isn’t one of quick wins, but of endurance, the kind that defines Europe’s new generation of deep-tech builders.

The company has spent over a decade building hard technology at the frontier, and persistence and the ability to remain flexible under pressure have turned it into a superpower.

“The world is big and we know there will always be someone smarter out there,” Svilen says. “But the secret is that the winners are those who never, ever give up.”

In deep tech, that might be the most scalable advantage of all.

.svg)