When a company issues additional shares, this inevitably reduces the shareholding percentage of some or all of the existing shareholders (i.e. founders as well as prior investors). In startup and VC terminology, the affected shareholders are being diluted by the entrance of additional shareholders.

Equity dilution can be a positive thing when valuations rise and existing shareholders see the economic value of their piece of the company pie go up (despite their percentage shareholding being diluted). But the situation changes drastically when companies are pressured into raising rounds at lower valuations (so called down rounds). Instead of just reducing the percentage ownership of existing shareholders, such a scenario can in addition lead to a decline in the economic value of prior investments in the company.

We’ve already answered the frequently asked question, “What is equity dilution?” This included the difference between percentage dilution and economic dilution as well as the effects of up rounds and down rounds on a company’s cap table. Now, I want to dive a bit deeper into how investors might seek to protect themselves against the negative consequences that could arise from dropping valuations and excessive dilution caused by down rounds.

I know it sounds convoluted, but we’re going to break down this complex topic while keeping the math to a minimum.

What is anti-dilution protection?

The legal documents that are drawn up for early-stage financing rounds will almost always include a shareholders’ agreement (SHA), which outlines how the company is to be operated and covers various rights and obligations of the company’s shareholders. In the context of startups, the SHA usually includes a subset of so-called “investor protection” provisions, which cover not only special voting/veto rights and liquidation preferences but may also include specific anti-dilution clauses. The purpose of the latter is to protect an investor’s shareholding in case of a down round by granting them the right to receive additional shares (basically) for free.

Our general observation is that while such clauses may not be particularly common at the pre-seed stage, investors will usually request some form of protection from the seed-stage onwards. As a general rule of thumb: The bigger the ticket an investor writes and the riskier the venture, the more important it will be for such an investor to negotiate anti-dilution provisions (as well as other forms of investor protection rights). In addition, turbulent economic periods may also reduce the risk of appetite among investors and could lead to anti-dilution provisions being more in the spotlight compared to recent years.

Anti-dilution protection ≠ Pro rata right

Before diving into the details of anti-dilution provisions, it’s important to understand that shareholders usually have a (contractual or even statutory) right to participate in future equity rounds in order to keep their percentage shareholding unchanged. However, this so-called pro rata right is exercised at the terms of the respective financing round. For example, if existing shareholders exercise their pro rata rights in a Series A round, they will acquire additional shares for the Series A share price.

While this also results in some sort of dilution protection, it can get very expensive for early investors to keep up with their pro rata rights as valuations (hopefully) rise exponentially in follow-on rounds. The kind of anti-dilution clauses that I will discuss below, however, are a form of extra protection for investors in case of a down round, allowing existing shareholders to subscribe for additional shares for free (or only against payment of nominal amounts).

Anti-dilution clauses

Now let’s take a closer look at how you can expect anti-dilution clauses to function in practice. As previously hinted, their primary purpose is to protect certain existing investors against the economic dilution that can result from a down round. That is, in case shares are issued at a lower price than the price per share that was paid by the existing shareholder. This is achieved by granting such existing investors the right to receive additional shares (referred to here as “anti-dilution shares'') for free in the course of a down round.

The previous paragraph is referring to “certain existing investors” because anti-dilution protection is usually only granted to specific share classes. Typically such rights are limited to the newest class of preferred shares. For instance, if anti-dilution protection is included in the shareholders agreement for a Series A round, the protection will usually only apply to the Series A share class(es).

However, it’s also possible to contractually agree for the anti-dilution protection to apply to all outstanding preferred shares. When it then comes to a down round, the protection will apply to all preferred shareholders that have paid a higher share price than the price per share that is paid in the down round.

Different calculation methods

The big question now is: How many “free” shares can an existing investor expect to receive in case their shares are indeed covered by the contractual anti-dilution protection?

There are essentially three different approaches for calculating the number of anti-dilution shares that yield substantially different outcomes depending on the circumstances of a specific company and its cap table structure. We will now take a closer look at each of the three calculation methods and the results that would be reached by applying these different approaches to the shareholding of the Series B Investor from the example that was discussed in the first part of this article.

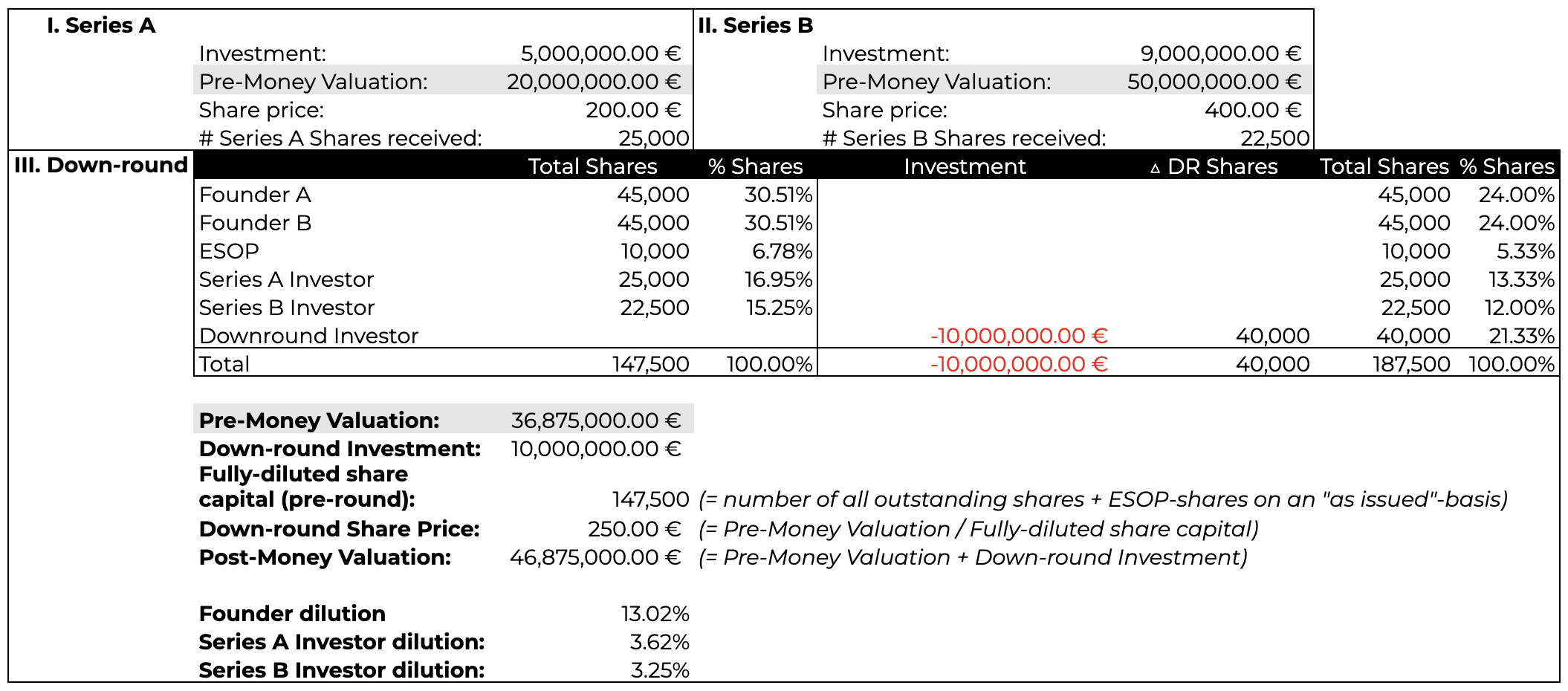

To illustrate the different calculation methods, I will continue the example from our look at equity dilution. As a quick reminder: The company in question has raised a Series A, followed by a successful (i.e. up round) Series B. Thereafter, due to an overall tougher fundraising environment, the company raises a down round. Below you can find a brief summary of the what happened in our example up to and including the down round:

One quick disclaimer upfront: The exact formulas used can differ from agreement to agreement and law firm to law firm. However, the general concepts shown below should be applicable irrespective of different drafting styles.

Full-ratchet

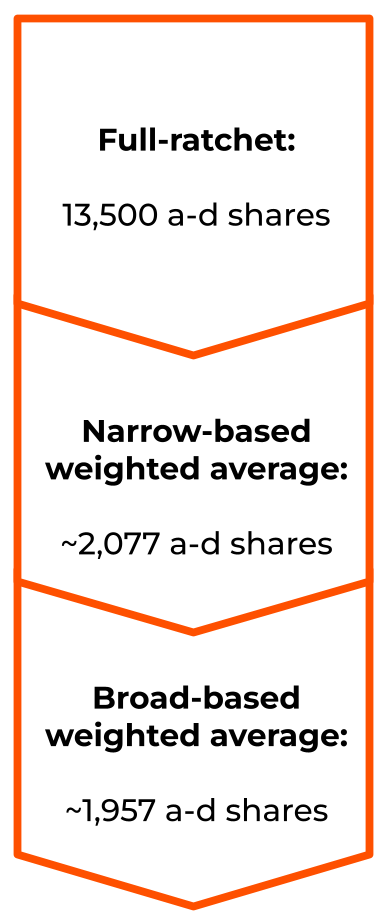

The first method is the so-called full-ratchet anti-dilution protection. This is not only the least founder-friendly approach by far, but also the least relevant in practice. You should basically never see a full-ratchet clause in your financing agreements. And if you do, then that should raise a reg flag in your head..

In short, the goal of a full-ratchet mechanism is to put earlier investors in the position they would have been in, had they invested at the share price of the down round. The diluted shareholder therefore gets to reprice its full investment at the new (lower) share price of the down round. The difference between the result of this calculation and the number of shares actually held by the affected shareholder at the time would then constitute the number of anti-dilution shares to be issued as compensation for the economic dilution occurring because of the down round.

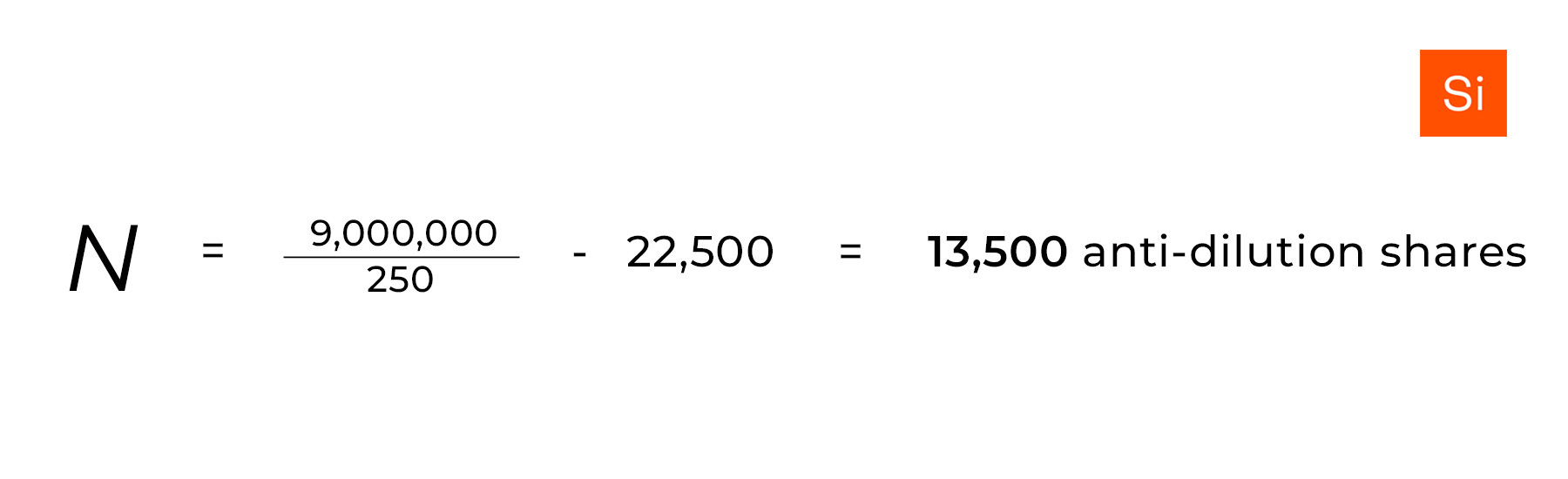

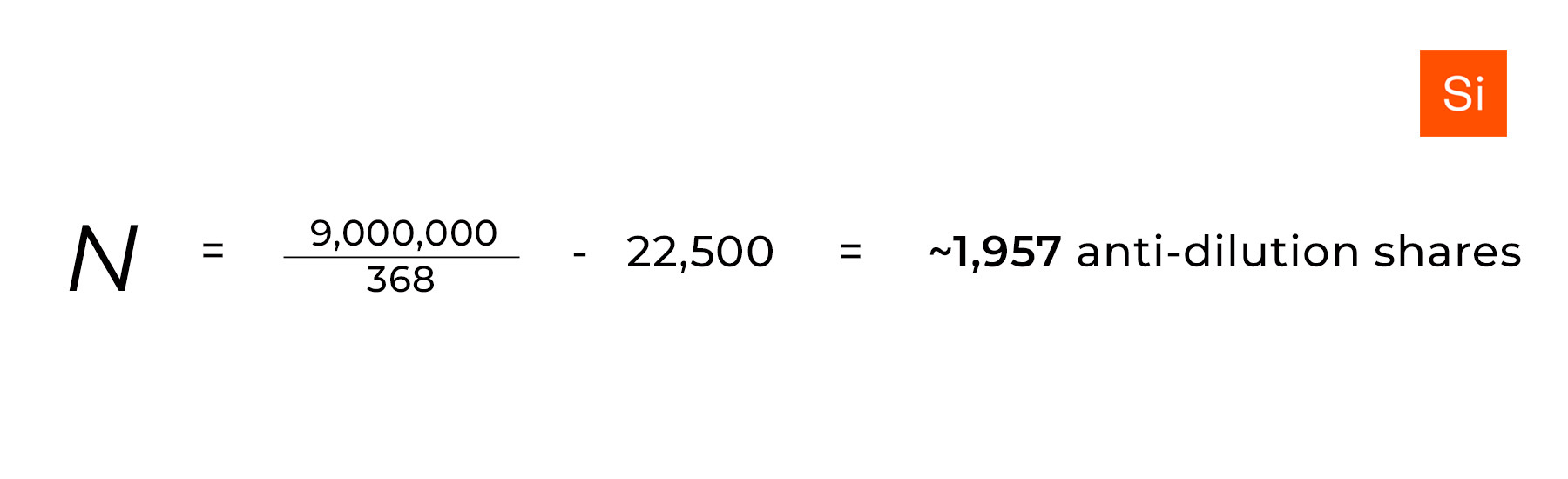

As mentioned above, the entire investment amount of the Series B Investor would be divided by the share price of the down round. When you then subtract the number of shares currently held by the respective investor (i.e. 22,500), you would end up with the number of anti-dilution shares to be issued to the Series B Investor under a full-ratchet scheme.

Broad-based weighted average

On the other end of the spectrum, the most widely used form of anti-dilution protection is the broad-based weighted average protection. As this is most likely the type of provision that you will find in your future financing agreements, we will take a closer look at an example formula.

The basic concept revolves around calculating a weighted average share price that will end up somewhere in between the share price that was paid by the investor (usually the last round’s share price) and the share price that will be paid in the down round. In a second step, you then calculate the number of shares that the existing investor would have received, if the respective investment had been made at this blended share price. The difference between this number and the number of shares the respective investor currently holds will then be issued to the diluted investor.

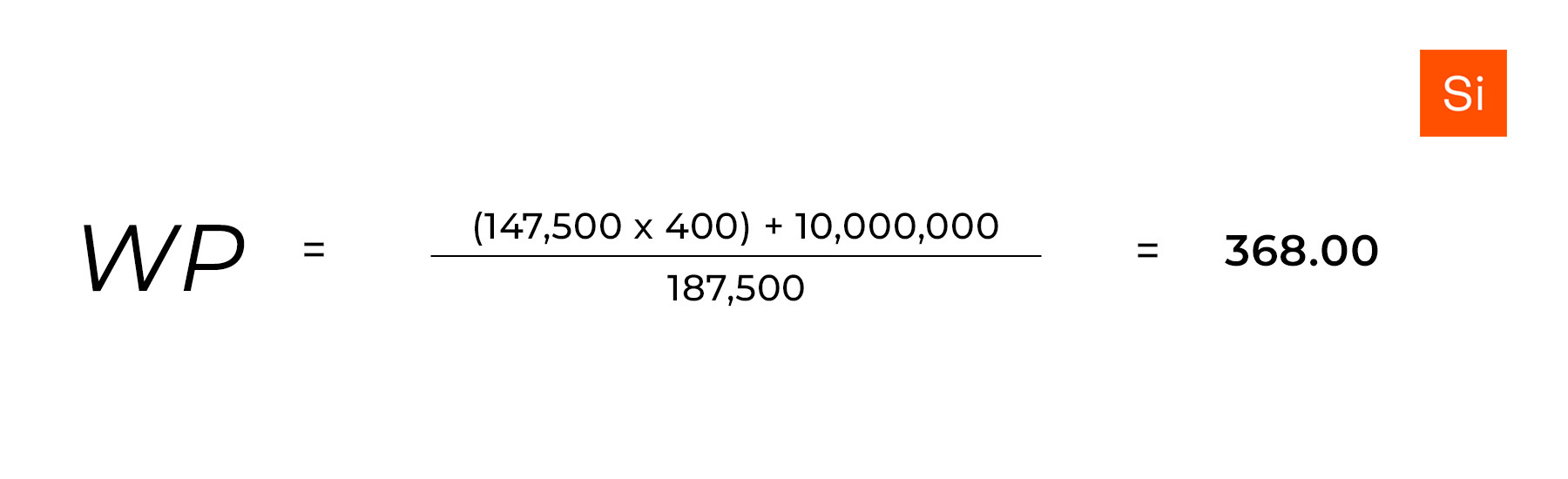

Now onwards to the fun stuff! The two-part formula for a broad-based weighted average anti-dilution scheme may look something like this:

.jpg)

As for the various terms and acronyms that are being thrown around here:

N = Number of anti-dilution shares to be issued

Ii = Investment amount paid by the investor

Si = Number of relevant preferred shares held by the investor

WP = Weighted average share price

IE = All shares outstanding prior to the down round (on a fully diluted basis) multiplied with the relevant preferred share price (that is protected under the anti-dilution clause)

ID = Total investments made by the all investors participating in the down round

S = Sum of (i) all shares outstanding prior to the down round (on a fully diluted basis) and (ii) all shares issued in the down round

The fact that this method takes into consideration not only the lower share price of the down round, but also the (higher) issue price of the protected class of preferred shares, leads to the broad-based weighted average protection being a much more balanced approach compared to a full-ratchet calculation.

Example (Series B Investor):

Narrow-based weighted average

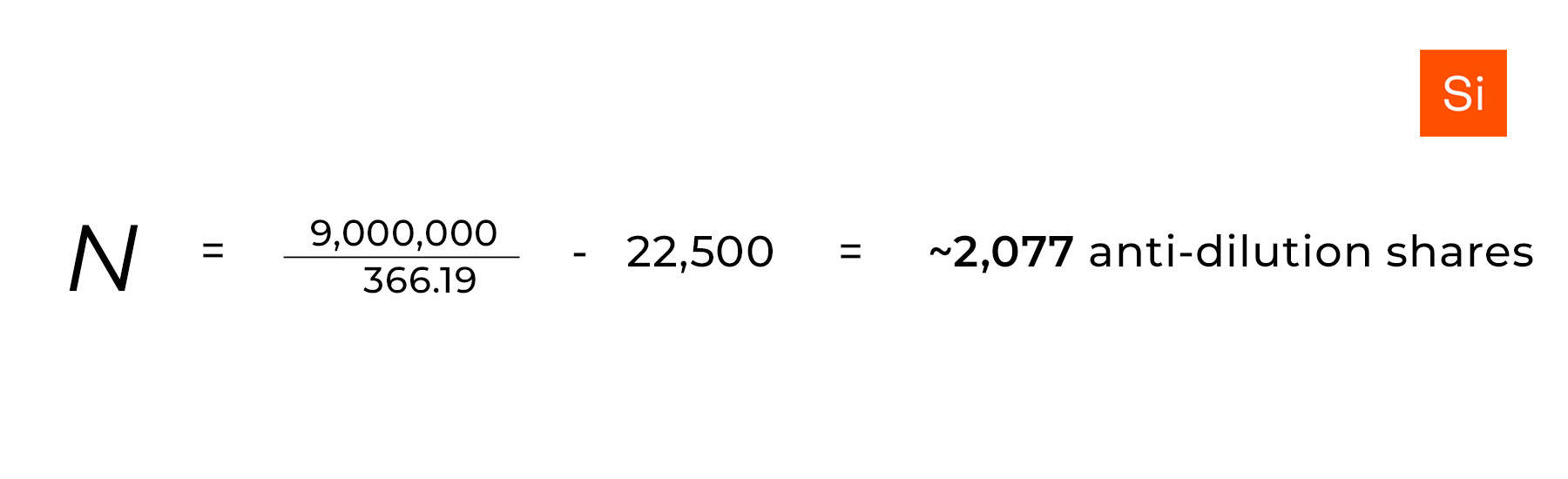

Last but not least, a few words on the narrow-based weighted average protection. This method for calculating anti-dilution shares is for the most part identical to its broad-based relative with one notable deviation.

The part of the formula that is “narrower” is the number of outstanding shares that is part of the values “IE" and “S”. While the broad-based weighted average formula refers to the fully diluted shares (i.e. including options), the narrow-based formula only considers shares actually issued at the time. The resulting weighted share price should end up somewhere in between the share price of the down round and the price calculated via the broad-based weighted average formula.

Example (Series B Investor):

.jpg)

As a result, the narrow-based approach is less favorable to founders compared to the broad-based approach, but still preferable over a full-ratchet calculation. Depending on the commercial terms of prior (up)rounds as well as the down round, the difference especially between a full-ratchet scheme and the weighted average methods can be quite significant, as can be seen from the perspective of the Series B Investor in our short example.

As already mentioned, the vast majority of deals that we have seen over the last few years include some form of broad-based weighted average protection. Whether this market standard will change more towards narrow-based weighted average protection due to a shift in negotiation power resulting from changing economic conditions is still up in the air.

Stylistic differences between the European Union and the United States

Please note that the aforementioned formulas and explanations are focused primarily on what we see in central European companies and transactions. Under this “EU-model,” anti-dilution clauses usually grant a right to subscribe for additional (preferred) shares in the course of a down round to make up for excessive dilution (either for free or for paying only the nominal amounts for such shares, depending on the jurisdiction).

In the US however, a different approach is usually considered market standard. While the general concept is quite similar, the standard US-model is built upon modifying the so-called conversion ratio, which is the ratio at which preferred shares may be converted into common shares. Upon issuance, this is a 1:1 ratio (i.e. upon conversion, an investor receives one common share for every preferred share). By way of very similar formulas to the ones described above, this ratio can be increased as a result of a down round. Thus, investors do not immediately receive additional preferred shares in the course of the down round, but their “as-converted” shareholding is increased accordingly.

In US financing rounds that are based on NVCA documentation, the anti-dilution clause can be found in the amended Certificate of Incorporation. (see cl. 4 of the NVCA model CoI, which can be found here).

Key takeaways and the importance of cap tables

While some form of dilution is unavoidable and even desirable for existing shareholders, that’s not the case for excessive economic dilution, which can result from valuation drops (or even stagnation). In order to have at least some degree of protection for down round scenarios, specific clauses may be included in the legal documents that form the basis of a financing round.

You should not fear or automatically reject any proposed investor protection clauses, but rather try to understand the actual content of such a provision, its potential consequences on the company’s cap table, and get a feeling for what is (and what is not) reasonable. Consider that VCs and other institutional investors have their own due diligence requirements towards their respective shareholders as well as certain legal/regulatory obligations––meaning not all protective clauses are proposed out of pure greed.

My rather general suggestion for every founding team would be to get acquainted with cap tables as early as possible. Model your own cap table and keep it meticulously up to date. My personal suggestion would be to first familiarize yourself with the basic mechanics and calculations in Excel. Subsequently, it can make sense to take advantage of specialized cap table tools. For example, one of our portfolio companies, Ledgy, makes developing cap tables and ESOP calculations easy.

In the context of cap tables, you’ll also want to make regular use of scenario analysis to see for yourself what different structures and contractual schemes could result in. This massively helps to evaluate questions like whether an employee stock option plan should be set up before or after an equity round, or (coming back to the topic of this post) what effect a specific anti-dilution clause could have in a flat- or down round.

And last but not least, when the next financing round is around the corner, make sure you do your term sheet due diligence, understand what equity dilution is, and do not forget to involve experienced VC lawyers and make active use of their expertise.

DISCLAIMER: The content of this article (including any models provided herein) is solely for informational purposes and may not be construed as legal, tax, investment, financial, or other advice. The opinions expressed at or through this site are the opinions of the individual author and may not reflect the opinions of Speedinvest or any of its affiliates.